read also

Spring Break shifts toward private luxury villas: trend changes

Spring Break shifts toward private luxury villas: trend changes

Albanian rents rise as investment returns fall

Albanian rents rise as investment returns fall

Italy Raises Flat Tax to €300,000

Italy Raises Flat Tax to €300,000

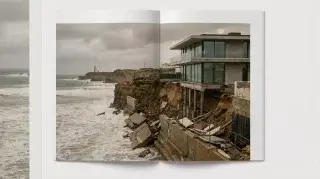

Storm Kristin Reprices Portugal Property Risk

Storm Kristin Reprices Portugal Property Risk

London Heathrow Airport: 228 Delays and 48 Flight Cancellations

London Heathrow Airport: 228 Delays and 48 Flight Cancellations

Batumi Housing Market: Prices Rose by 17% in 2025 — TBC Capital Report

Batumi Housing Market: Prices Rose by 17% in 2025 — TBC Capital Report

New York’s affordable housing crisis: $1 billion needed to prevent a wave of defaults

Photo: Unsplash

New York may need $1 billion to prevent defaults among affordable housing providers, Bloomberg

reports, citing the New York Housing Conference. Operating costs are rising faster than regulated rent levels, leaving a substantial portion of the affordable housing stock in financial distress. A planned rent freeze is expected to intensify pressure on operators and accelerate deterioration in building conditions without urgent city intervention.

The affordable housing sector in New York is under unprecedented strain. Maintenance expenses are surging, while rent levels regulated by the Rent Guidelines Board remain mostly stagnant. Tens of thousands of units out of 213,000 subsidized by the city and state are already running deficits as costs for water, electricity, fuel and insurance significantly outpace revenue. This has led to mounting debt and a heightened risk of defaults, especially among operators who have no ability to offset losses through market-rate rentals.

The situation is further aggravated by the proposed rent freeze for 1 million stabilized apartments introduced by Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani. While the measure may support renters, it increases the likelihood of defaults among operators of fully affordable buildings, who lack mechanisms for cross-subsidization. According to the Housing Conference, key expense categories — utilities, energy and insurance — cannot be reduced, meaning that any drop in income immediately affects building maintenance and long-term sustainability.

Experts note that the current stress is the result of a decade-long divergence between costs and regulated rent growth. For many years, the affordable housing financing model relied on predictable, gradual increases in regulated rent. Over the past decade, however, rent growth has nearly stalled, while operating costs accelerated sharply, creating a structural gap that has now become critical.

Rachel Fee, Executive Director of the Housing Conference, emphasizes that stress levels in the sector are the highest in twenty years. In eight of the last twelve years, the Rent Guidelines Board approved rent increases of less than 2%, while insurance premiums rose by an average of 25% annually. The rise reflects nationwide trends driven by climate-related risks and the shrinking number of insurers, making insurance one of the key drivers of financial instability. Pandemic-era arrears widened the gap further, while current budget parameters prevent operators from compensating for escalating expenses without external support.

Mamdani’s team states that the city can protect tenants while simultaneously supporting housing providers struggling with rising costs. Officials point to existing hardship exemptions and tax incentives for buildings undergoing infrastructure upgrades. They also acknowledge the urgent need to address high insurance premiums and tax imbalances that place additional burdens on affordable housing operators.

According to Housing Conference estimates, approximately $1 billion will be required in 2026 to restructure accumulated debt. The organization urges the city to support a collective insurance structure modeled after Milford Street, simplify access to reserve funds, expand rental assistance, extend tax incentives for renovations and freeze water rates. Another proposed measure involves revising rent levels on vacancy-cycle units, many of which are currently frozen below thresholds outlined in regulatory agreements.

Small property owners warn that current conditions threaten not only the viability of their businesses but also the availability of affordable units. Anne Korchak, chair of the Small Property Owners of New York, stresses that prolonged financial pressure drives operators off the market, reducing options for renters and undermining the city’s entire affordable housing framework.

Additional pressure comes from the broader reconfiguration of the rental market. The median rent for new leases in Manhattan in August reached $4,600 — down 2.1% month-over-month but up 8.4% year-over-year. The rise pushes renters to search for more affordable options outside central Manhattan. Median rent in Brooklyn increased by about 8% to $3,950, and in northwest Queens — by nearly 7%, to $3,775. The shift in demand increases competition in these neighborhoods and amplifies pressure on landlords working under fixed or tightly regulated rent structures.

The situation is complicated by the implementation of the Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses Act, which bans broker fees for tenants when the broker is hired by the landlord. After the law came into effect, the number of vacant units dropped by 9% in a single month, as some owners temporarily withdrew inventory from the market. Realtors report that landlords are already raising asking rents by 8–12% to offset additional expenses — an option unavailable to operators of stabilized or fully affordable buildings. This deepens the divide between the free market and the affordable housing sector, where rent growth is constrained by strict regulations.

Analysts at International Investment highlight that the combination of accelerating operating costs, stagnant regulated rents, a shifting rental landscape and tightening rules is pushing New York’s affordable housing sector toward a systemic crisis. The gap between expenses and revenue is widening faster than the city can adapt support mechanisms. Under these conditions, the stability of the affordable housing system depends directly on large-scale government intervention. Without external funding and targeted regulatory adjustments, preserving the supply and quality of affordable housing will be increasingly difficult.