читайте также

German Economy to Rebound in 2026

German Economy to Rebound in 2026

European Hotel Operating Profit: Margins, RevPAR and Costs

European Hotel Operating Profit: Margins, RevPAR and Costs

US housing construction fell to its lowest level since May 2020

US housing construction fell to its lowest level since May 2020

Snow Cyclone “Francis” in Russia: Widespread Disruptions at Airports and on Roads

Snow Cyclone “Francis” in Russia: Widespread Disruptions at Airports and on Roads

Canada tightens scrutiny at land crossings: Asylum claims show a clear decline

Canada tightens scrutiny at land crossings: Asylum claims show a clear decline

Wealthy Americans eye New Zealand luxury homes: Ban lift reshapes the top end of the market

Wealthy Americans eye New Zealand luxury homes: Ban lift reshapes the top end of the market

Вusiness / Real Estate / Investments / Analytics / Research / Germany / Real Estate Germany 14.09.2025

Housing in Germany: Rents Are Rising While Investment Yields Decline

In the first half of 2025, rents in Germany grew faster than wages, and the number of new apartments coming to market fell short of demand. BNP Paribas Real Estate’s report emphasizes that this gap shaped market conditions, even as the share of household income spent on rent remained lower than in many other European countries.

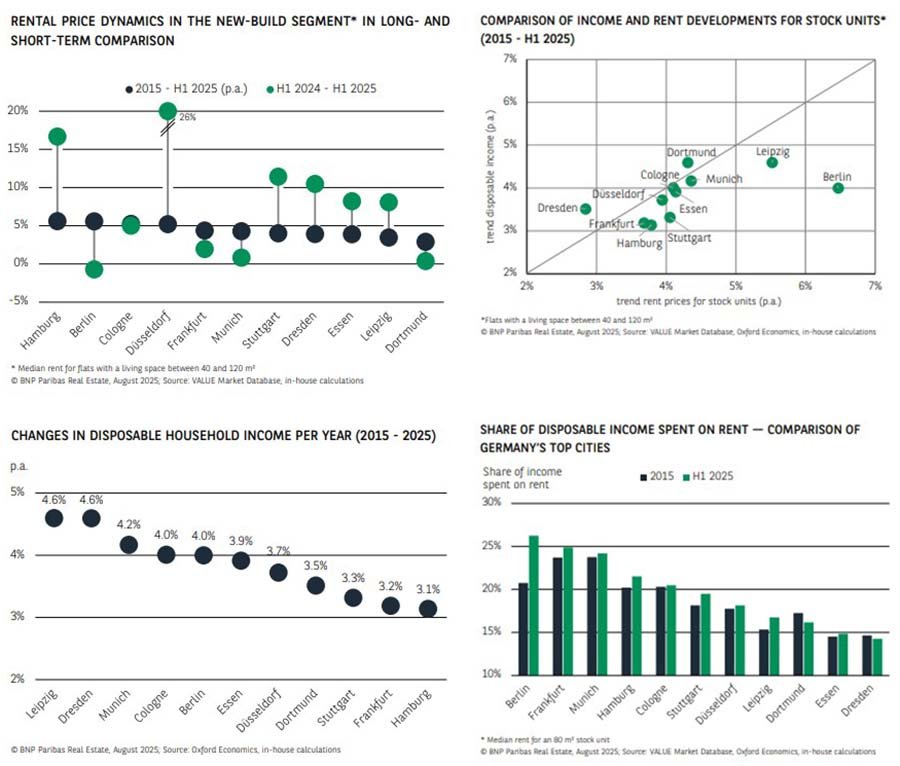

Price Dynamics and Incomes

From January to June 2025, asking rents for new-builds rose by an average of 8% year-on-year. For comparison, across 2015–2025 the increase in the largest cities averaged about 4.4%. The existing-homes market showed a similar picture: over the last decade, rents climbed roughly 4.3% per year, but 2025 growth outpaced those long-term averages.

Among the largest cities, Hamburg and Düsseldorf saw the fastest increases in rents. A key factor was a wave of higher-end apartments entering the market, immediately shifting average rent levels upward. Strong growth also appeared in B-cities—major regional hubs outside the “top-7.” In Leipzig, Dresden, and similar locations, new-build rents rose by 8–10% versus January–June 2024, with Dortmund the notable exception.

Household incomes in the largest cities grew by an average of 3.8% per year over the decade, but rent growth outpaced income almost everywhere. In Hamburg, earnings increased by just 3.1%. In Berlin, incomes rose by about 4% annually, while existing-home rents were up 6.5%—the widest gap. In Munich, wages rose 4.2%, yet housing costs still climbed faster. Dresden posted a notable 4.6% rise in incomes; only there and in Dortmund did income growth slightly outpace rent increases, improving tenant affordability. In Leipzig, the rates were 4.6% versus 5.5%.

In Berlin, the share of income spent on housing increased from 21% in 2015 to 26% in 2025—the most pronounced change. In Düsseldorf, Cologne, Munich, and Essen the level stayed roughly the same, while Dresden and Dortmund even improved. Net result: in six of Germany’s eleven largest cities, rental affordability did not deteriorate.

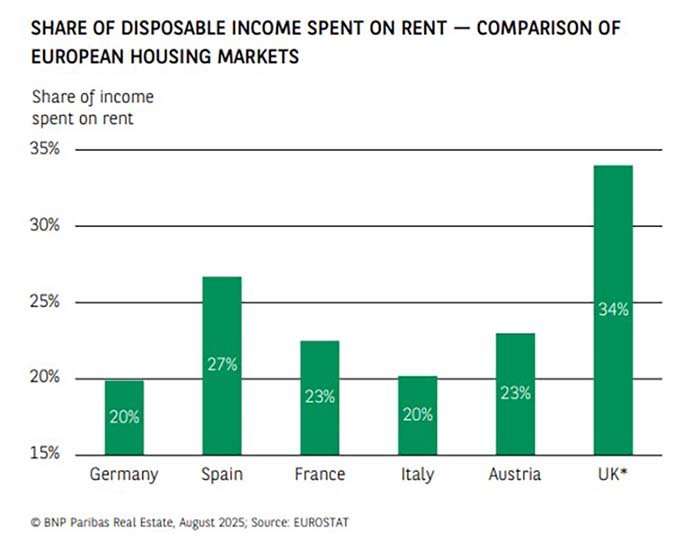

On average, German renters allocate about 20% of income to housing. For comparison: the UK is at 34%, Spain 27%, and both France and Austria 23%. Faster real income growth in Germany over the past two years partially offset accelerating rent increases.

Vacancy and Median Rents

Vacancy fell to 2.5% in 2023 and remains below the 3% threshold generally seen as the minimum for a balanced market. In Munich and Frankfurt, empty apartments are practically nonexistent—just 0.1%. By contrast, in cities with the highest vacancy levels—Pirmasens (8.3%), Dessau-Roßlau (8.0%), and Frankfurt (Oder) (7.5%)—the gap versus the leaders exceeds eight percentage points.

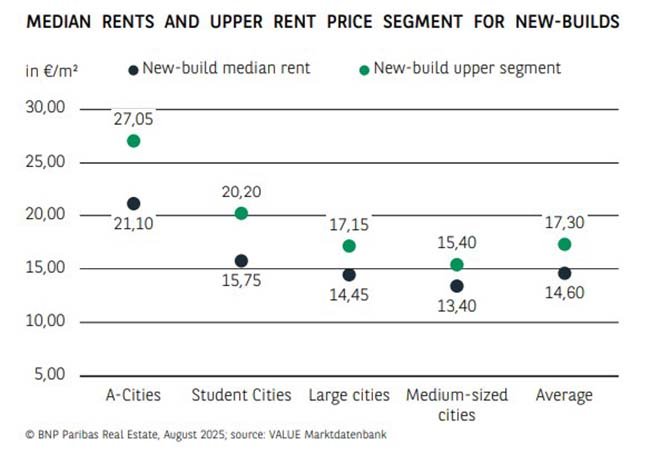

In 2024, 252,000 new apartments were completed—42,000 fewer than a year earlier. Meanwhile, the number of households increased by 162,000, widening the demand–supply imbalance. In H1 2025, average asking rents for existing stock reached €10.35/sq m (+4% vs. 2024). In new-builds, the median rose 7% to €14.65. In “A-locations” (top-7 cities), existing-stock rents climbed to €15.75 (+4%); in student cities to €12.25 (+4%); in large regional centers to €10.45 (+5%); and in mid-sized cities to €9.50 (+3%).

In the largest cities, the average asking rent hit €21.10/sq m, up €1.30 since the start of the year. At the top end, the gap widened: student cities now price 14% above the national median, and A-locations 13% above. The most expensive markets are Munich (€24.50), Hamburg (€22.40), Berlin (€20.90), and Frankfurt (€20.85).

Since 2015, asking rents in existing stock have risen by an average of 49%, and in new-builds by 55%. The sharpest decade-long increase is in Berlin (+87%), followed by Rostock and Kempten (+73%), Leipzig (+71%), and Amberg (+69%). New-build rents are up 55% overall, led by Berlin (+72%), Hamburg (+67%), and Düsseldorf (+66%).

Even with rising rents, net yields are easily eroded by regulation, operating expenses, and capex. At high purchase multiples (25–26× annual rent in A-locations), any slip in occupancy, pricing, or financing costs can push a leveraged project into negative territory.

1) Regulatory Constraints (Pressure on Rent Growth)

— Rent controls and caps. Indexation is bounded by local Mietspiegel/Kappungsgrenze; adjustments are spread over time and often fail to cover cost inflation.

— Scrutiny of index-linked leases. Indexmietverträge increase payment volatility for tenants—raising the risk of political pushback or targeted restrictions down the line.

— Short-let rules. Zweckentfremdung restrictions in major cities limit Airbnb/serviced apartments and remove the “short-stay premium.”

Investments

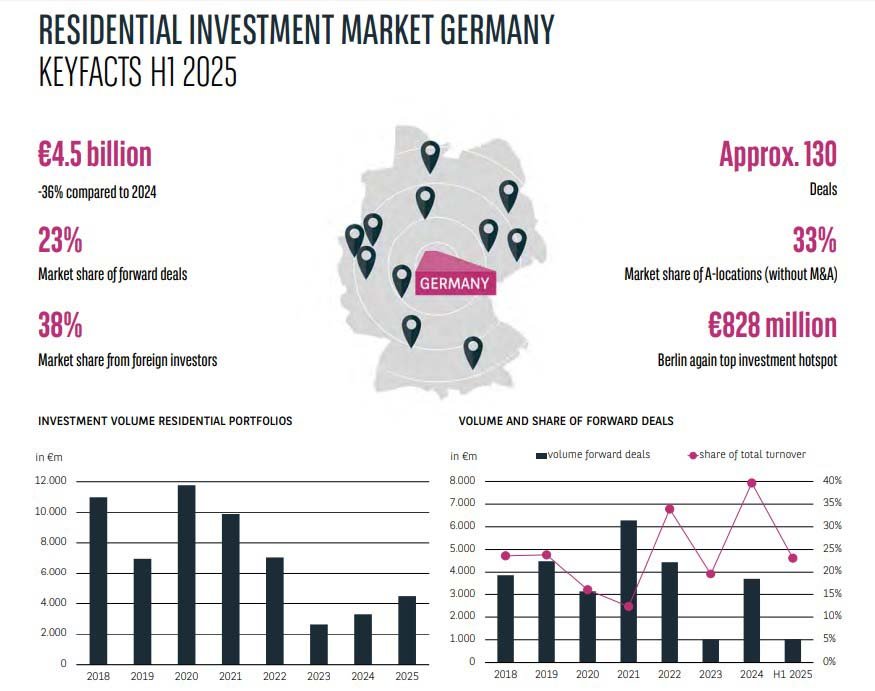

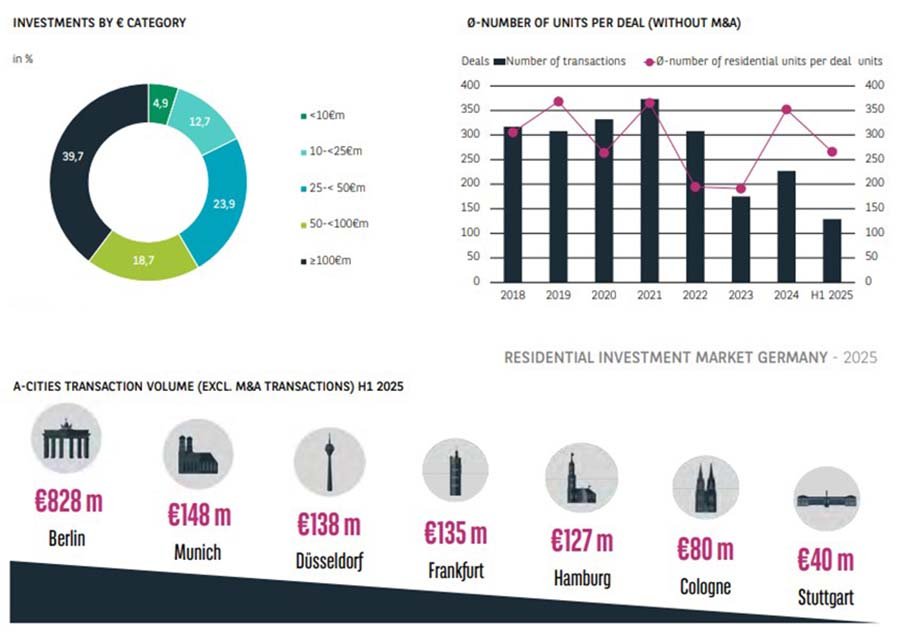

About 130 transactions totaling €4.5 billion closed in January–June 2025—36% less than the same period in 2024 and roughly one-third below the ten-year average. Forward deals (projects acquired during construction) fell to 23% of volume. At the same time, large bundles of completed assets gained share, accounting for 38% of deals with foreign investors. US buyers, in particular, showed renewed activity—seen as a sign of recovering confidence in Germany’s real estate market after a slowdown.

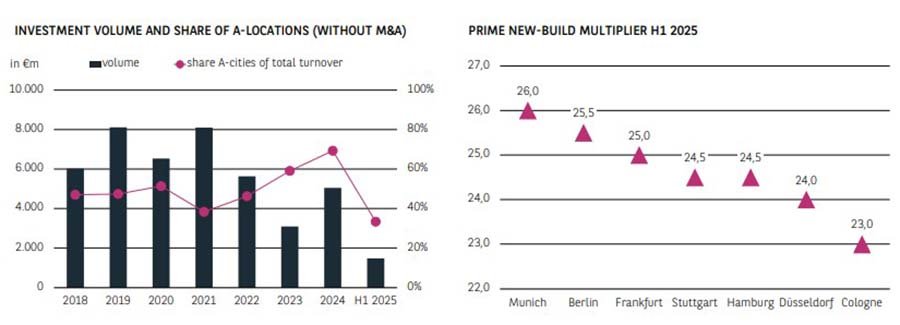

A-locations (Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Stuttgart) captured just 33% of transactions versus a ten-year average of 47%, reflecting strong portfolio activity and limited supply in top cities.

Berlin reaffirmed its position as the largest hub with €828 million invested (18% of national volume). Munich ranked second (€148 million), followed by Düsseldorf (€138 million), Frankfurt (€135 million), Hamburg (€127 million), Cologne (€80 million), and Stuttgart (€40 million).

New projects in the largest cities are priced by “multiples”—the number of annual gross rents required to buy an asset. Munich remains the most expensive at 26×. Berlin stands at 25.5×, Frankfurt at 25×, Hamburg and Stuttgart at 24.5×, Düsseldorf at 24×, and Cologne at 23×.

4) Yield vs. Cost of Capital (Negative Leverage Risk)

— Multiples of 24–26× in Munich/Berlin/Frankfurt imply a gross yield around 3.8–4.2%. After vacancy, 5–7% management, common-area costs, insurance, and taxes, net yield can slide to 2.5–3.2%.

— With financing costs that, even after easing, remain above pre-crisis levels, a negative spread emerges: cost of debt ≥ net yield. The model requires either aggressive value-add or a discount on entry.

Conclusion

Germany’s rental market remains under significant pressure, especially in the largest agglomerations. The core issue is a persistent construction slump: fewer new apartments are being delivered even as the population grows—particularly over the last two years. This intensifies supply–demand imbalances and accelerates rent growth. New-builds show the sharpest increases, reflecting limited completions, strong demand, and higher construction costs. The pressure is likely to persist over the next few years and may even strengthen if building activity weakens further. Rents should therefore continue rising, especially in the largest cities and in new-build stock.

The investment segment is also reorganizing. H1 2025 brought more transactions and a greater share of large portfolios, alongside a return of interest in value-add assets—signs of a shift to a new recovery phase. In H2, more activity and closings of deals postponed earlier in 2025 are expected. Analysts see full-year transaction volumes potentially reaching the low double-digit billions. Even so, yields may compress further as competition for quality assets intensifies amid scarce supply.