read also

Evacuation from the Middle East: How Countries Are Bringing Their Citizens Home

Evacuation from the Middle East: How Countries Are Bringing Their Citizens Home

Japan Corporate Bankruptcies Hit 13-Year High

Japan Corporate Bankruptcies Hit 13-Year High

Japan’s New Condo Prices Reach Record High

Japan’s New Condo Prices Reach Record High

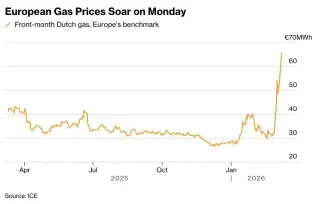

European Gas Prices Surge Amid Middle East War

European Gas Prices Surge Amid Middle East War

EU prepares new foreign investment screening rules

EU prepares new foreign investment screening rules

Collapse of Air Travel in the Middle East

Collapse of Air Travel in the Middle East

Migration / Ratings / Research / Analytics / Sweden / Finland / Portugal / Belgium / Spain / Germany 07.10.2025

Migrant Integration Index 2025: Europe Is Losing Momentum

The integration policies of EU countries have slowed down. The average score in the new MIPEX 2025 Index increased by only 0.8 points — to 54 out of 100, according to the study by the Migration Policy Group. Sweden, Finland, and Portugal remain the leaders. The countries that joined the EU after 2004 are far behind — averaging 44 points compared to 63.

Who Fights Discrimination

The strongest policy areas remain anti-discrimination (78 points), permanent residence (61), and access to the labor market (55). The weakest are citizenship and political participation — 44 and 37 respectively. Between 2019 and 2023, there was minor improvement in education and employment, but a decline in citizenship and political engagement.

Anti-discrimination (78) — the maximum 100 points were awarded to Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, Portugal, and Romania. In the “very favorable” group are Spain, Sweden, and Slovenia (92–96), as well as Hungary and Ireland (around 85). Even in countries with lower results — France, Italy, and Germany — scores remain above 65. The least developed equality protection mechanisms are found in Denmark, Estonia, and Lithuania (around 50).

Permanent Residence (61) — the best conditions for obtaining long-term status are found in Finland (96) and Sweden (90). Hungary rose unexpectedly high — 81 points, ahead of Belgium (79) and Spain (75). In the mid-tier group are Portugal (71), Bulgaria (69), Estonia and Italy (67 each), and Slovakia (65). Slightly lower are Slovenia, Luxembourg, Romania, France, and Germany (54–58). Other countries — including Poland, Czechia, and Austria — hover around 50 or below. The lowest scores were recorded in Latvia (46) and Denmark (42).

Labor Market Mobility (55) — Portugal, Finland, and Sweden lead with over 90 points, ensuring migrants nearly equal access to employment and qualification recognition. Germany also ranks high (81). Most Eastern European countries remain in the lower tier. Above-average performers include Spain, Italy, Denmark, and notably Estonia — the only new EU member with a stable high score (69). Lithuania scored 52, Latvia only 33. Slovakia (17) and Ireland (22) are in the “unfavorable” category.

Family Reunification (53) — Portugal offers the most open policy (93 points), followed by Estonia (76), Sweden (71), and Finland (67). Moderately favorable conditions exist in Italy, Czechia, Spain, and Slovenia (60–63). The majority of countries fall in the middle: Slovakia (59), Hungary (58), Greece and Luxembourg (52 each), Poland (50), Belgium (48), Latvia and Ireland (46–47). Germany, France, and Lithuania rank near the bottom alongside Bulgaria, Austria, Malta, Cyprus, and the Netherlands. Denmark scores the lowest — 25.

Healthcare (53) — the best access to medical services for migrants is in Ireland (85), Sweden (83), and Austria (81). They are followed by Italy, Spain, Belgium, and Finland (71–75). Mid-range performers include Portugal, the Netherlands, and Germany (60–65), as well as France and Malta (around 55). Below-average: Czechia (52) and Romania (53). At the bottom: Estonia, Cyprus, Slovakia, and Poland (30–40). Latvia (25) and Hungary (17) close the list — with the most limited migrant access to healthcare.

Education (50) — Sweden ranks first (93), followed by Finland (88), Belgium and Portugal (74 each). The Nordic countries show the most systematic approach to inclusion and language support. Slightly lower are Estonia (69), Austria and Luxembourg (64), Czechia (62), the Netherlands (57), and Germany (55). Southern and Eastern states show modest results — 50–43 points. Bulgaria (21) and Hungary (0) close the list, with Hungary scoring the lowest in the entire EU.

Access to Citizenship (44) — Portugal leads (86), followed by Sweden (83) and Luxembourg (79). Ireland, Finland, and France are relatively liberal (70–74). Most others remain “halfway open”: Germany, Belgium, and Malta (65–52), the Netherlands and Cyprus (50). Below average — Poland (44), Denmark (41), Greece and Italy (40). In Eastern Europe, the figures drop sharply: Romania, Czechia, and Slovakia (around 30), Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia (19–22). Austria (13) and Bulgaria (9) have the most restrictive citizenship systems.

Political Participation (37) — Finland ranks first (85), followed by Portugal and Sweden (80 each). In the mid-range: Luxembourg, Belgium, Germany, and Denmark (60–65), Ireland and Spain (60). Below average: France (45) and the Netherlands (50). Most Eastern and Southern European countries score extremely low — from 25 in Malta and Cyprus to 5 in Czechia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Bulgaria.

Barriers Are Worsening the Situation

Researchers note that the scores were determined using the latest available year (2023 or 2024), and the EU average reflects 2023 data. The best integration results belong to Sweden (86), Finland (84), and Portugal (83) — countries combining strong rights guarantees with active inclusion policies. Belgium follows with 70 points. In the “slightly favorable” group are Spain (64), Germany and Luxembourg (61 each), Ireland (59), Italy (58), the Netherlands (57), and France (56).

Slightly below average: Romania and Slovenia (52 each), Estonia (51). Then Czechia, Denmark, and Greece (49 each). Malta scored 48, Austria 47, Croatia and Poland 44. In the “slightly unfavorable” group: Cyprus and Hungary (41 each), Bulgaria and Slovakia (39 each), Lithuania (37), and Latvia (36).

The report cites specific reforms that affected scores: Germany’s 2024 citizenship reform introduced dual nationality and shortened residency requirements. Spain’s 2022 anti-discrimination law strengthened the national equality authority.

Portugal and Croatia simplified family reunification; Slovenia and Greece reformed labor markets. Meanwhile, Luxembourg and Denmark weakened migrant advisory bodies, and Finland and Ireland limited civic participation programs.

Migration Policy Group’s research head Başak Yavcan notes that EU migrants often enjoy basic rights and some long-term protection but still lack equal opportunities. Progress has been noted in education and anti-discrimination, while access to citizenship and political participation remains alarming.

The arrival of Ukrainian refugees led to useful measures in health and education, but their broader, long-term impact remains limited. “If Europe wants to build a cohesive and future-ready society, investment in education, safe housing, and democratic integration cannot wait,” the expert emphasized.

Co-author Marianna Giorgerino adds that improvements are most visible where countries reduce barriers — for instance, speeding up qualification recognition or strengthening equality institutions. “Stricter rules on citizenship and family reunification risk leaving people in limbo and undermining long-term integration,” she warned.

Researchers urge governments to make integration investment a key element of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, and to reduce disparities between EU states. Priorities include expanding education and language programs, ensuring stable residence pathways, and enabling real civic participation. Strengthening anti-discrimination laws and equality institutions is also highlighted as crucial.

Подсказки: migration, MIPEX, EU, Sweden, Finland, Portugal, discrimination, integration, citizenship, politics, equality, migrants, Europe, Migration Policy Group