read also

Spring Break shifts toward private luxury villas: trend changes

Spring Break shifts toward private luxury villas: trend changes

Albanian rents rise as investment returns fall

Albanian rents rise as investment returns fall

Italy Raises Flat Tax to €300,000

Italy Raises Flat Tax to €300,000

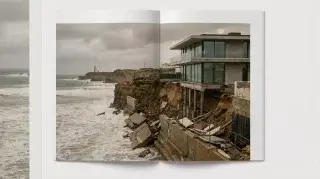

Storm Kristin Reprices Portugal Property Risk

Storm Kristin Reprices Portugal Property Risk

London Heathrow Airport: 228 Delays and 48 Flight Cancellations

London Heathrow Airport: 228 Delays and 48 Flight Cancellations

Batumi Housing Market: Prices Rose by 17% in 2025 — TBC Capital Report

Batumi Housing Market: Prices Rose by 17% in 2025 — TBC Capital Report

Buying Property in Italy: The Preliminary Contract and Key Risks

Photo: Smushcdn.com

Buying real estate in Italy remains attractive, but the process is full of pitfalls. From bureaucracy and hidden debts to illegal renovations — mistakes at any stage can lead to serious losses. A preliminary contract — the compromesso — helps protect the buyer’s interests by fixing the key terms of the deal and reducing the risk of unforeseen issues.

Proposta d’Acquisto vs. Compromesso

Many buyers mistakenly believe that a written purchase offer is equivalent to a preliminary contract. In fact, these documents serve different purposes and entail different legal consequences, as explained here.

Proposta d’Acquisto is the first formal step. The buyer pays a small sum — usually up to 5% of the price — to confirm serious intent. This document binds only the buyer. If the seller does not accept it in writing, the money is returned. If the offer is accepted, it becomes binding, but usually does not include all the details of the transaction.

Compromesso (or contratto preliminare di vendita) is a far more detailed document. It sets the exact price, property description, payment schedule, deadlines, and the amount of the main deposit. Once signed, both buyer and seller are legally obliged to complete the sale.

Registration for Maximum Protection

Signing the preliminary contract does not end the process. To make it enforceable against third parties, it must be registered with the tax authority — Agenzia delle Entrate. By law, this must be done within twenty days of signing.

Registration makes the contract public. It protects the buyer from actions by the seller who might otherwise try to sell the property to someone else or pledge it to a bank. Without registration, such scenarios are not excluded. That’s why registration is not a formality but a crucial step.

Deposit: Confirmation or Penalty

When signing the compromesso, the buyer pays a substantial deposit — typically 10–30% of the purchase price. Italian law distinguishes two types of deposits, with different consequences if either party pulls out.

Caparra confirmatoria is governed by Civil Code Art. 1385. If the buyer withdraws, the seller keeps the deposit. If the seller is at fault, they must return double the amount. In addition, the injured party may go to court and demand specific performance of the contract.

Caparra penitenziale is governed by Art. 1386. Here the deposit acts as a pre-agreed compensation. If the buyer withdraws, they forfeit the money but the seller cannot claim more. If the seller breaches, they return double the sum, and both parties’ obligations end there.

Key Clauses to Include

To avoid ambiguity, the compromesso should be as detailed as possible. It typically includes the parties’ names and addresses, their tax codes, the property’s full address, cadastral data, floor area, and any accessory premises such as a garage or cellar.

Mandatory seller warranties are essential. The seller confirms title history; the absence of encumbrances such as mortgages or seizures; and the property’s compliance with building permits. The contract must indicate the final price, the amount and type of deposit, payment schedule, and the date for the notarial deed (rogito). Cost allocation should be explicit: who pays the notary and taxes. Usually the buyer bears these costs, but the distribution should be stated in the contract.

Checks Before Signing

Before entering into a compromesso, a full legal due diligence is essential. This includes a title check and a review of all planning and building documents. It helps confirm that the property is free of hidden issues and complies with the law.

A key step is choosing the form of deposit — caparra confirmatoria or caparra penitenziale — because this determines the consequences of withdrawal. The buyer should insist that all provisions be drafted unambiguously and that the contract be registered with Agenzia delle Entrate.

For maximum protection, the contract can be executed with notarised signatures (scrittura privata autenticata) or drawn up entirely as a public deed (atto pubblico). These forms offer additional legal force and stronger guarantees for the buyer.

Bureaucracy and Delays

Even when procedures are followed strictly, Italian transactions rarely move fast. Despite gradual digitalisation, the process remains fragmented: different offices handle different documents; requirements vary by region; timelines depend on municipal workloads. As a result, even after signing the preliminary contract, it can take 3–6 months to reach the notarial deed.

For foreign buyers, the risks are even more tangible. Language barriers and the need to act through intermediaries can slow things further. Delays may lead to extra costs for temporary rentals, legal services, or repeat document checks.

Illegal Renovations

One of the most common risks is non-compliance with building rules. Estimates suggest that around 20% of Italian properties have unauthorised alterations: extensions, internal reconfigurations, or additions without permits — known as abuso edilizio.

After purchase, responsibility passes to the new owner. This can result in fines, lengthy legalisation procedures, or even orders to demolish unauthorised works. In the worst cases, confiscation is possible.

Hidden Debts and Liabilities

Even with a clean title, the buyer may inherit the previous owner’s debts — especially utility arrears and condominium charges. By law, new owners can be held liable for some of these obligations if they were not settled before transfer.

For foreign buyers, this can come as a surprise. Debts may surface after completion, when disputing them is difficult. Experts therefore advise always requesting debt-clearance certificates and including relevant warranties in the contract.

New Requirements and Penalties

In 2025, Italy tightened rules on energy performance and seismic safety. A valid set of certificates is now required for sale. If they are missing or contain inaccurate data, the buyer will bear the cost of updating them.

The property’s renovation history can also be an issue: if government incentives were used but works were non-compliant, the owner can be obliged to repay the subsidies. Buying an older property without document checks can therefore lead to substantial extra costs.

Litigation and Restrictions

If the transaction runs into breaches, dispute resolution in Italy can take years. Real-estate litigation may last 3–7 years, with legal fees running into hundreds of thousands of euros. Additional legal mechanisms can also restrict the buyer unexpectedly. These include right of first refusal (diritto di prelazione) for neighbours and various easements (servitù) requiring passage across the plot.

Pay particular attention to vincoli paesaggistici (landscape protection constraints) and rules requiring preservation of agricultural use. Such constraints can block renovations, prevent change of use, and sharply reduce market value.