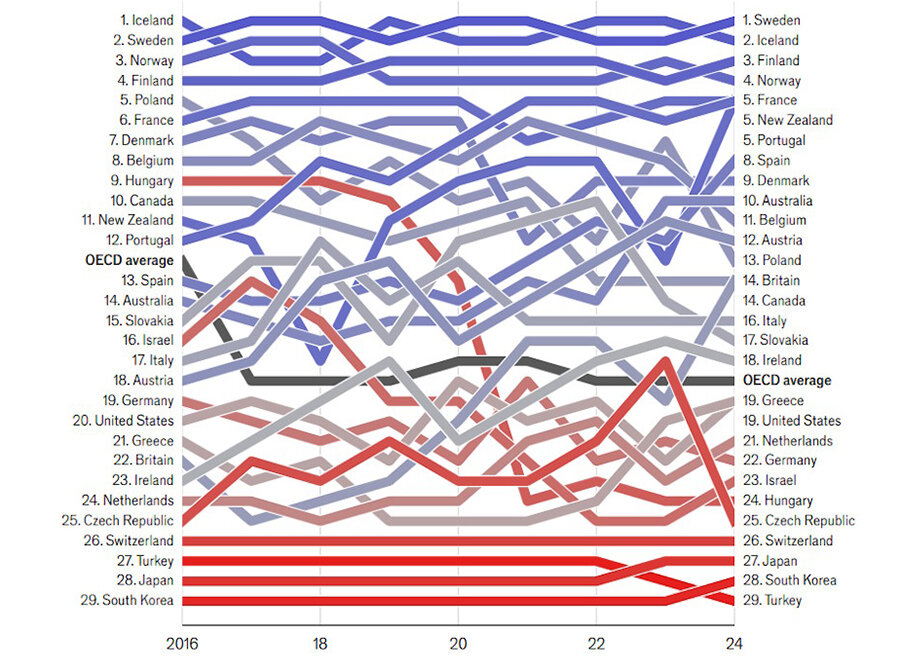

The Economist magazine published its "Glass Ceiling Index" (GCI) on International Women's Day. In the latest study, Sweden has surpassed Iceland, which had held the top spot for the past two years. Meanwhile, the U.S. landed in a disappointing 19th place, with below-average support for working women.

The Economist's GCI is an annual ranking of predominantly wealthy countries where women have the best chances of equal treatment in the workplace within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This year marks 13 years since The Economist first published the Glass Ceiling Index. Initially launched in 2013 with five indicators across 26 countries, the index now evaluates ten factors, including wages, education, parental leave, and leadership representation, covering 29 OECD nations.

Nordic Countries and Portugal Lead the Way

Sweden ranked first, followed by Iceland, while Finland, Norway, and Portugal rounded out the top five. Nordic countries continue to prioritize initiatives that support women in completing higher education, securing employment, advancing into leadership positions, and benefiting from comprehensive parental leave and flexible work policies.

Portugal improved its ranking significantly—its gender pay gap stands at just 6.1%, much lower than the OECD average, while childcare costs remain affordable. France, however, slipped in the rankings, as the proportion of women in executive roles and parliamentary seats slightly declined, whereas it increased in most other countries.

Japan, Turkey, and South Korea have remained at the bottom of the list for the 11th consecutive year. Deep-rooted societal norms and persistently high wage gaps contribute to this trend. These three countries notably have the lowest percentage of women in leadership roles—with fewer than 17% in executive positions, less than 20% in parliaments, and under 21% on corporate boards.

In 2024, New Zealand, the UK, and the U.S. showed the most improvement. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic and Belgium declined compared to last year.

Key Highlights from The Economist GCI

Maternity Leave

For the first time, the average fully paid maternity leave duration across OECD nations exceeded 30 weeks, reaching 31.6 weeks. In Hungary, it stands at 78.9 weeks—the highest among OECD nations.

The United States remains the only OECD country without federally mandated paid parental leave. Instead, American workers rely on the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which guarantees only 12 weeks of unpaid leave for eligible employees. While some U.S. states have introduced paid maternity leave programs, a nationwide system remains out of reach.

South Korea expanded its maternity and parental leave by seven weeks, while Norway, Portugal, and Spain also increased their parental leave benefits.

Paternity Leave

Across 29 OECD countries, the average paid paternity leave is 7.9 weeks, with Japan leading at 31.1 weeks. The U.S. offers no paid paternity leave.

The report highlights the importance of paternity leave, noting that when only women take extended leave, it reinforces traditional gender roles, limits women's career progression, and signals to employers that women are less committed to their jobs. This dynamic perpetuates the gender pay gap and limits female representation in leadership.

Most Expensive Countries for Parents

The U.S. ranks third among the most expensive countries for parents, with childcare costs consuming about 30% of the average wage. This financial burden falls disproportionately on women, who still bear the majority of caregiving responsibilities. Without affordable childcare, many women are forced to choose between career growth and family obligations.

Education for Women

The education gap between men and women widened by 8.1 percentage points—45% of working-age women in OECD countries hold a college degree, compared to 36.9% of men. Canada has the highest rate of female higher education attainment at 70.1%, followed by Ireland, Sweden, and the U.S., where over 50% of women hold university degrees.

However, women remain underrepresented in MBA programs, which are often seen as stepping stones to leadership roles and higher salaries. Despite earning more degrees than men, fewer women take the GMAT exam, a key requirement for MBA admissions. In the U.S., only 36.2% of GMAT test-takers are women. Finland is the only country where more women than men take the exam.

Elections

With several major elections in 2025, the average proportion of women in national parliaments across OECD countries has increased to 34%. Japan and the UK saw notable gains, with Japan's female parliamentary representation rising from 10% to 16%, and the UK increasing from 35% to 41%.

In contrast, the U.S. experienced a slight decline, with female representation falling to 28.7%.

Women in Leadership

According to The Economist, women hold 43.7% of executive positions in Sweden, 43% in Latvia, and 42.9% in the U.S.. The proportion of women on corporate boards has grown to 33%. The best-performing countries in this category include New Zealand (48%), the UK (44%), and Scandinavian nations.

Norway became the first country in the world to introduce corporate gender quotas in 2005, requiring that at least 40% of board members be women. Several other countries have since adopted similar measures.

Workforce Participation

The female labor force participation rate has increased to 66.6%, up from 65.8% last year. Iceland and Sweden lead, with over 80% of women in the workforce. At the bottom are Turkey (40.8%) and Italy (57.6%).

Gender Pay Gap

The gender pay gap remains at 11.4%, having steadily declined each year until the COVID-19 pandemic. In Australia and Japan, it has slightly worsened.

The U.S. ranks 25th out of 29 OECD countries for pay equality—American men earn 16.4% more than women. Only four countries—South Korea, Israel, Japan, and Finland—have larger gender wage gaps.

Gender Disparity Persists

The gender pay gap remains stagnant over time, with minimal progress in the past eight years. This suggests that structural barriers continue to hold women back.

Among the most pressing issues:

- Lack of paid parental leave or insufficient leave duration.

- Persistently low wages for women.

- Gender biases and outdated stereotypes.

Experts conclude that time alone will not close the gender gap—meaningful change requires political reforms and cultural shifts.