United Kingdom on the Brink of a New Debt Crisis

Photo: Unsplash

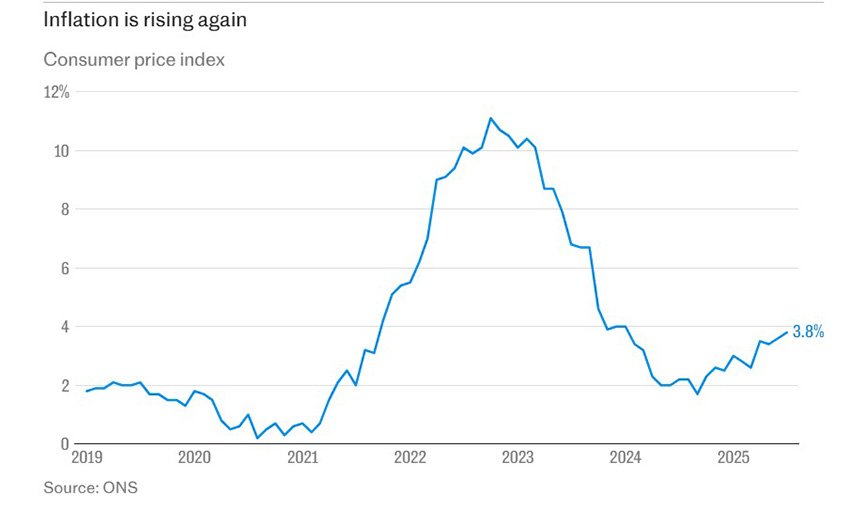

The United Kingdom risks repeating the debt crisis of the 1970s, with a current budget deficit of £50 billion (€67.5 billion), writes The Daily Telegraph. The country may once again require an International Monetary Fund bailout. Inflation is rising, and new tax measures could lead to stagflation, undermining investor confidence.

Leading economists compare Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves’ policies to those of Denis Healey in 1976. At that time, Britain turned to the IMF for a loan to stabilize the pound and cover budget expenses, agreeing in return to severe cuts in government programs, including the halting of municipal housing construction.

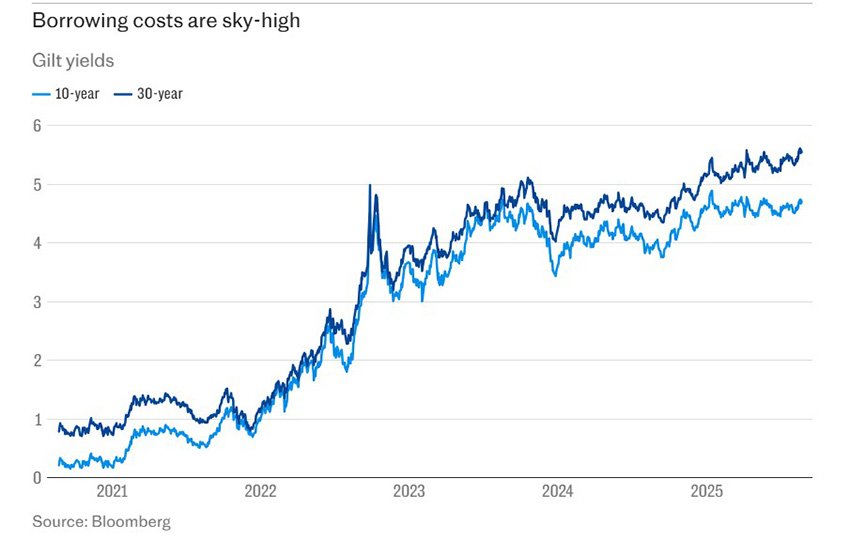

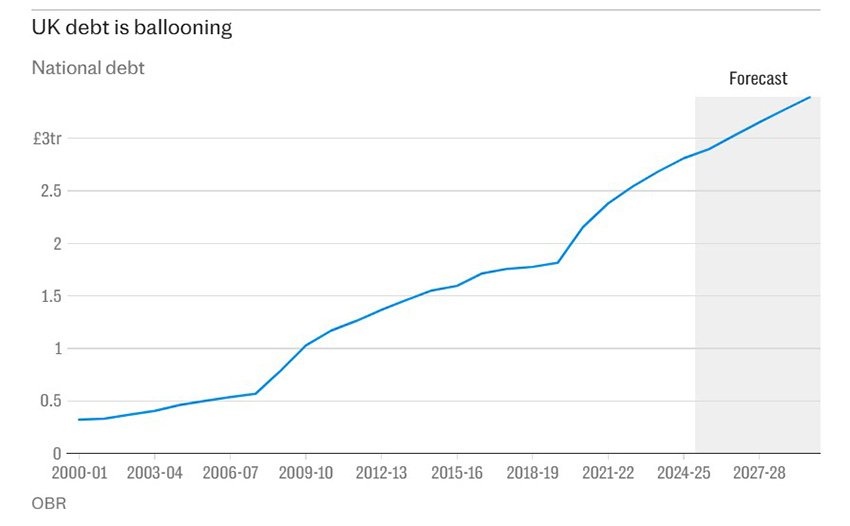

In 2025, the UK government is again seeking to close a £50 billion deficit through further tax hikes. Britain ranks fifth globally in debt-to-GDP ratio at 96.3%. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, debt servicing costs will reach £111.2 billion in 2025, or one in every twelve pounds of public spending. Yields on 30-year government bonds have surpassed 5.5%—a level last seen after Liz Truss’s disastrous “mini-budget.”

Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch said rising borrowing costs are the price of “ineffective economic management” by Labour. Reform UK leader Nigel Farage warned the country is “in a debt spiral” and that further tax hikes will accelerate the path to an “economic doom loop.”

Professor Jagjit Chadha, who recently stepped down as head of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, warned of collapse: “We will not be able to restructure debt, we won’t be able to pay pensions, and benefits will become difficult to sustain.” Former Bank of England MPC member Andrew Sentance also criticized Reeves’ policy, saying simultaneous tax hikes and spending increases fuel both demand-pull and cost-push inflation. He noted that UK bond yields are now higher than in the US and even Greece, reflecting investor skepticism toward Britain’s economy.

Willem Buiter, another former MPC member, suggested the Chancellor will be forced this autumn to break her campaign promises and raise key taxes—income tax, VAT, and others—to ease pressure on the debt market. This could help rein in yields and stabilize investor confidence.

Business groups are also raising concerns. The British Retail Consortium, representing major chains, warned that current fiscal policies could lock food price inflation at 5% for another year. CEO Helen Dickinson emphasized that higher corporate taxes would mean stagflation—a mix of weak growth and persistently high inflation. International lenders are already raising borrowing costs for the UK due to its ballooning debt.

Officials reject claims of an imminent debt crisis, noting that the IMF itself has endorsed the current strategy. The “Plan for Change” includes reducing borrowing and investing in key social sectors, and interest rates have already fallen five times in recent months.

Bloomberg reported that the IMF has advised Britain to charge wealthier citizens for NHS services and reconsider generous pension guarantees. The report came shortly after the OBR warned of unsustainable long-term fiscal trends.

Particular attention was given to the “triple lock” mechanism, which raises pensions by the highest of three metrics—inflation, wage growth, or a 2.5% minimum. According to OBR, the scheme already costs £15.5 billion annually, triple initial estimates. Meanwhile, healthcare and disability benefit costs are set to reach £100 billion by decade’s end. IMF analysts recommend linking pensions only to living standards and introducing partial NHS co-payments for affluent citizens.

The IMF did praise the government for efforts to reform welfare spending. However, plans to cut costs by £5 billion ($6.7 billion) were shelved after Labour MPs objected. While IMF experts called the budget bold and growth-oriented, they left forecasts unchanged: GDP growth of 1.2% in 2025 and 1.4% in 2026. High interest rates and rising savings are expected to limit consumption, while global trade conflicts may hinder investment.

Подсказки: UK economy, UK debt crisis, IMF, budget deficit, stagflation, Rachel Reeves, UK politics, bond yields, pensions, NHS