Ireland’s Income Tax Deadlock. A structurally strained tax system

Photo: Irish Times

Ireland’s debate over income tax intensified in 2025, exposing deep structural weaknesses in the country’s fiscal model. Public perception remains divided between those who feel overburdened and those who believe high earners contribute too little. The issue is further complicated by the central role of property in household wealth, where income levels do not always reflect underlying financial security.

This sense of imbalance is reinforced by widespread dissatisfaction with public services, which many taxpayers believe fail to justify the level of taxation imposed. High-profile spending controversies have amplified these concerns.

The problem of a low top-rate threshold

Ireland’s 40 per cent top income tax rate is not, in itself, unusually high by international standards. Even when combined with USC and PRSI, marginal rates compare broadly with those in other advanced economies. The real source of tension lies in the low income threshold at which the higher rate applies.

At approximately €44,000, the threshold sits well below the State’s median wage, pushing large numbers of middle-income earners into high marginal tax bands much earlier than in comparable countries.

A narrowing tax base

Recent Department of Finance reports highlight the growing concentration of income tax receipts. The top 10 per cent of earners now generate around 40 per cent of income tax revenue and 60 per cent of USC receipts, while the bottom half of earners contributes only a small fraction.

More strikingly, around one-third of all income earners, equivalent to about 1.2 million tax units, fall effectively outside the income tax net due to generous tax credits. This significantly narrows the tax base and increases reliance on a relatively small group of taxpayers.

Political constraints on reform

Broadening the tax base by drawing in lower-paid workers would be politically explosive, particularly given high housing costs and rental pressures. Increasing the burden on the squeezed middle is also seen as untenable, while further taxing high earners risks undermining Ireland’s competitiveness in attracting mobile talent and investment.

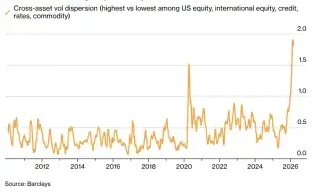

Across Europe, governments are increasingly competing for high-net-worth individuals through targeted tax incentives, adding another layer of complexity to domestic reform efforts.

Turning to property taxation

As a result, attention has increasingly turned to shifting part of the tax burden from labour to property and wealth. Advocates argue that labour should be taxed more lightly, as it is more productive and socially beneficial, while property remains undertaxed in Ireland.

The Commission on Taxation and Welfare has previously recommended increasing taxes on property and wealth to broaden the tax base. However, Ireland’s local property tax remains low by international standards, and recent valuation reforms have deliberately limited the impact of rising house prices on household tax bills.

Corporate tax as a temporary cushion

The government’s ability to delay difficult reforms is largely underpinned by windfall corporation tax receipts, which have masked underlying weaknesses in the income and property tax systems. These revenues have provided fiscal breathing space but also increased vulnerability.

The Department of Finance has repeatedly warned that reliance on corporation tax is risky and potentially unsustainable. Should these revenues decline, the structural flaws in Ireland’s tax system are likely to become far more acute.

As reported by International Investment experts, Ireland’s current tax model increasingly depends on a narrow base and volatile revenue streams. For investors and property owners, this raises the likelihood of future tax reform, with property and wealth taxes among the most probable targets for adjustment in the years ahead.