read also

Nearly 1,900 Affordable Apartments Sit Empty in Portland Amid Housing Crisis

Photo: Wikimedia

In Portland, nearly 1,900 subsidized apartments remain vacant despite long waitlists for affordable housing and a growing homeless population. Vacancy in this segment exceeds 7%, well above the level the real estate market typically considers balanced. The contrast is especially stark given continued budget investment in housing programs and ongoing new construction, analysts at CoStar note.

High vacancy as a sign of imbalance

In Portland, 1,863 subsidized apartments are sitting empty, representing 7.4% of the city’s affordable housing stock. For a segment designed for low-income renters, that level of vacancy is considered unusually high. In professional practice, around 5% is often viewed as a balanced level, where supply and demand are in relative equilibrium and units are occupied without meaningful downtime.

Exceeding that threshold points to a gap between the formal existence of subsidized units and their real-world accessibility for the intended audience. In a context where demand is confirmed by multi-thousand waitlists and rising homelessness, vacancy becomes an indicator of management and administrative failures within the affordable housing system.

The situation becomes even more acute given the scale of funds already committed. The number of vacant units is comparable to the amount of housing expected to be created through a $258 million bond measure approved by Portland voters in 2016. This raises the risk that expanding construction without changing leasing and placement mechanisms will not reduce the structural shortage.

A structural breakdown in housing allocation

High vacancy in Portland’s affordable housing stands in sharp contrast to the scale of real demand for housing assistance. When the housing authority Home Forward reopened its Housing Choice Voucher waiting list in spring 2025 for the first time in nearly two years, there were roughly seven applications for every available spot. That level of pressure points to strong, accumulated demand among low-income households.

At the same time, waitlists capture only the portion of the population able to navigate the formal application process. The real need is much broader and is reflected in homelessness statistics. According to Multnomah County, more than 16,000 people lack permanent housing, including about 7,500 who are unsheltered—living on the streets or in cars. Most of them are concentrated in Portland, further intensifying pressure on the city’s housing market.

Rising homelessness is occurring in parallel with an increasing volume of unused subsidized inventory. This dynamic suggests a missing link between emergency measures such as temporary shelters and pathways that move people into permanent housing. Even when apartments physically exist, the system does not ensure fast, large-scale lease-up.

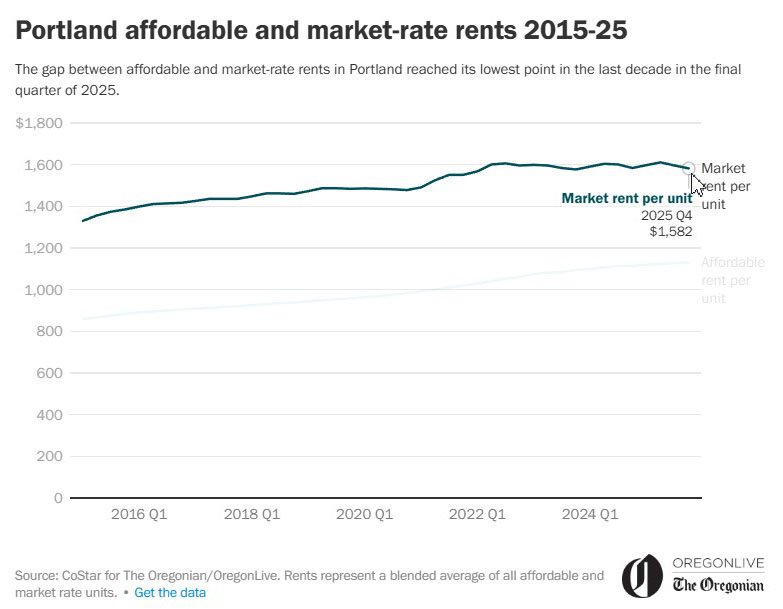

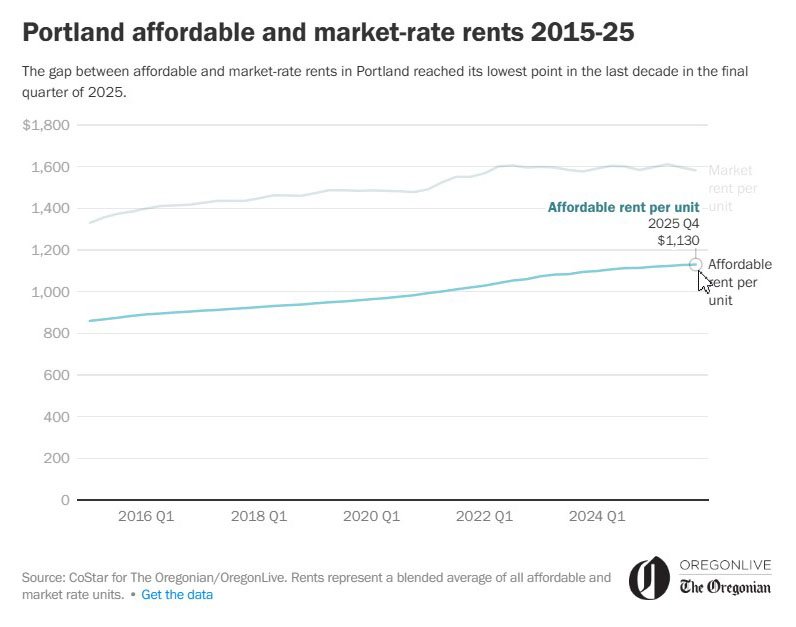

Rent convergence erodes the price advantage

One key driver of rising vacancy has been the narrowing gap between subsidized and market rents. By the end of 2025, the average difference in Portland had fallen to $452, the lowest level in the past decade. For many renters, the financial advantage of affordable housing no longer compensates for the associated constraints and bureaucratic procedures.

The most vulnerable segment has been housing aimed at households earning up to 60% of area median income. In this range—especially for studios—rents are often comparable to market levels. With market rents stagnating in conventional apartment communities, renters near the income eligibility threshold can choose between formally “affordable” housing and the open market without a meaningful cost difference.

Market-rate properties also win on non-price factors. Leasing is simpler, there is no annual income recertification, and amenities and service levels are often stronger. As a result, subsidized housing loses its competitive edge at precisely the moment it is expected to function as a stabilizing mechanism for vulnerable groups.

What operators and officials are saying

Affordable housing operators openly argue that current rent levels no longer match what the target population can pay. Margaret Salazar, CEO of Reach Community Development, stresses that even subsidized rents can be out of reach for some of the lowest-paid households. She says this pushes people to stay with relatives or friends instead of moving into formally “affordable” apartments.

Analyst data also confirms the shrinking price advantage. Yardi Matrix reports that about 42% of market-rate apartment communities in the Portland metro area offer rents within 10% of affordable housing rents. Paul Fiorilla, the firm’s director of research, notes that at this level of competition, subsidized housing becomes less attractive—especially given more complex leasing procedures.

Property managers echo that view. Tom Brenneke, president of Guardian Real Estate Services, which manages both market-rate and affordable properties, points to an imbalance in administrative burden. He says renters increasingly prefer market-rate buildings where paperwork is minimal, while subsidized programs require extensive documentation and ongoing reporting.

City officials acknowledge the issue but emphasize its institutional nature. Gabriel Matthews of the Portland Housing Bureau notes that for renters at roughly 60% of median income, market-rate options can be a rational alternative, particularly amid rent stagnation in that segment. He also points to a rise in evictions within affordable housing after pandemic-era rent support programs ended, increasing tenant turnover and system strain.

The national context

Portland’s situation fits into a broader national picture in which the affordable housing shortage is driven not only by construction volumes but also by the limited throughput capacity of existing programs. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the US in 2025 is

short about 7.1 million affordable and available homes for extremely low-income households.

On average nationwide, for every 100 extremely low-income households there are only about 35 homes that are both affordable and actually available to rent, the organization reports. In West Coast states, including Oregon, that ratio is below the national average, increasing pressure on municipal housing systems and making them more sensitive to lease-up failures within the existing stock. Renters’ financial constraints further narrow effective demand. The same organization notes that more than 70% of extremely low-income households spend over half of their budgets on rent. Under these conditions, even subsidized housing can remain out of reach without additional support or lower operating costs.

What this means for investors

Analysts at International Investment note that Portland’s case reflects a broader transformation in housing policy: affordability is increasingly determined not by how much is built, but by management quality and financial mechanisms. With market rent growth slowing and price levels converging, operational efficiency becomes a key driver of occupancy. Without adjustments to current tools, affordable housing risks remaining formally delivered but effectively inaccessible to the target audience.

For investors, Portland demonstrates a shifting risk profile for affordable housing projects. Even with strong social demand and government participation, such assets can carry elevated vacancy, directly affecting cash flows and income predictability.

As affordable rents converge with the market, the resilience of affordable housing as a defensive asset declines. Returns increasingly depend on administrative processes, lease-up speed, and the stability of budget support—shifting risk from the market domain into institutional and operational execution.

Read also:

Affordable housing rental crisis in New York: $1bn needed to prevent defaults

New-build shortage in Manhattan: Upper West Side down 94%

US real estate investment: housing leads, industry with logistics and retail

The most challenging areas to live in the US