read also

Spring Break shifts toward private luxury villas: trend changes

Spring Break shifts toward private luxury villas: trend changes

Albanian rents rise as investment returns fall

Albanian rents rise as investment returns fall

Italy Raises Flat Tax to €300,000

Italy Raises Flat Tax to €300,000

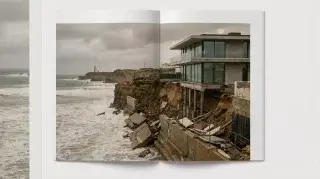

Storm Kristin Reprices Portugal Property Risk

Storm Kristin Reprices Portugal Property Risk

London Heathrow Airport: 228 Delays and 48 Flight Cancellations

London Heathrow Airport: 228 Delays and 48 Flight Cancellations

Batumi Housing Market: Prices Rose by 17% in 2025 — TBC Capital Report

Batumi Housing Market: Prices Rose by 17% in 2025 — TBC Capital Report

Rent Caps in France May Be Extended and Expanded

Photo: Unsplash

French lawmakers propose extending limits on rent increases and applying them to more cities, reports Le Figaro. The experiment was launched in 2018 and covered 72 municipalities. It was initially scheduled to end in November 2026, but members of parliament now have a different view.

The initiative’s authors are MPs Annaïg Le Meur (Ensemble pour la République) and Iñaki Echaniz (Parti Socialiste). In their report, they propose making the mechanism permanent and allowing its rollout not only in high-demand zones but also in neighbouring municipalities. According to them, most communes where regulation already applies report positive results.

The report stresses that rent control is not the cause of declining supply. A drop is observed even in cities without regulation. The main goal is not to reduce prices but to prevent excessive increases. According to the Paris Urbanism Agency (APUR), between July 2023 and June 2024 the average rate in the capital was 8.2% lower than the forecast level without regulation. Over this period, tenants saved an average of €1,700 per year thanks to the mechanism.

Lawmakers are preparing a bill based on the report and a parallel economic study commissioned by the government. Proposals include granting all mayors in high-demand zones and their suburbs the right to introduce regulation, as well as setting transparent coefficients for additional areas such as terraces, cellars, or mezzanines.

Echaniz noted that surcharges for exceptional features—terraces, cellars, or panoramic views—most often become the subject of litigation. The report proposes publishing court decisions to simplify practice for landlords and agents. Measures are also envisaged to adjust the base rent, counter circumvention via co-living and shared leases, and protect tenants from unjustified lease terminations.

According to Manuel Domergue, Research Director at Fondation Abbé Pierre, the document is an important step for tenants. He emphasised that the work is cross-party and should lead as soon as possible to a law that enshrines rent control on a long-term basis. In the parliamentary mission’s final report, the mechanism is described as sound and beneficial, and its extension is recommended not only for Paris, Lille, Lyon, or Bordeaux but for all high-pressure zones, as Le Monde writes.

Professional associations (UNPI, Unis, SNPI) insist that the experiment has expanded without adequate assessment, generating “administrative cumbersomeness” and legal uncertainty. They point to rising risks for landlords, investor outflows, and shrinking supply. The same source notes that the simultaneous effect of several measures—prefectural caps, the annual decree under Article 18 of the 1989 law, and the IRL index cap (3.5%)—together squeeze yields and encourage apartment sales instead of renting.

The industry also criticises the mechanism’s practical side: owners increasingly resort to extra charges for “exceptional characteristics” such as balconies, terraces, or cellars. This has become the subject of numerous court disputes. Professional groups warn that tightening the rules will double fines (up to €10,000 for individuals and €30,000 for legal entities), extend tenants’ challenge periods, and close loopholes through co-living or civil-law rental contracts. Experts believe such measures will further destabilise the market.

Additional challenges concern compliance in practice. Almost 43.2% of rental listings in Paris are advertised at prices above the caps. Even after court rulings, tenants do not always recover overpaid amounts: owners drag out the process or exploit legal gaps. As a result, many tenants prefer not to contest violations, reducing the mechanism’s effectiveness.

Economists also highlight side effects, as noted: holding down rents in some segments triggers “demand spillover” into other, unregulated niches—e.g., higher-comfort flats or areas without caps—where prices rise faster due to limited supply and stronger demand. Over the long term, this can deepen the divide between regulated and free markets.

The methodology for calculating base rents raises questions as well. Analysts argue it lacks transparency and relies on averaged data that do not always reflect local conditions. In some cases, outdated datasets produce distorted values and many exceptions. As a result, both tenants and owners face difficulties applying the rules in practice.

France is not alone. Athens, Barcelona, Copenhagen, and other European capitals face a similar problem: rapid rent growth driven by supply shortages and the influx of tourists and digital nomads. In some cities, rents have risen by more than 30% in five years, prompting resident protests and EU-level discussions of restrictive measures.

For investors, the prospect of expanded regulation entails additional risks. Tighter controls and higher fines will constrain pricing freedom and reduce the appeal of rental investments. Professional groups already warn that a mix of caps and complex calculation methods pushes owners to sell rather than rent. If the mechanism is enshrined in law, this process may accelerate, shrinking private supply and increasing pressure on the market.

Подсказки: France, rent control, housing policy, Paris, rental market, tenants, landlords, regulation, IRL, APUR, Le Figaro, Le Monde, real estate